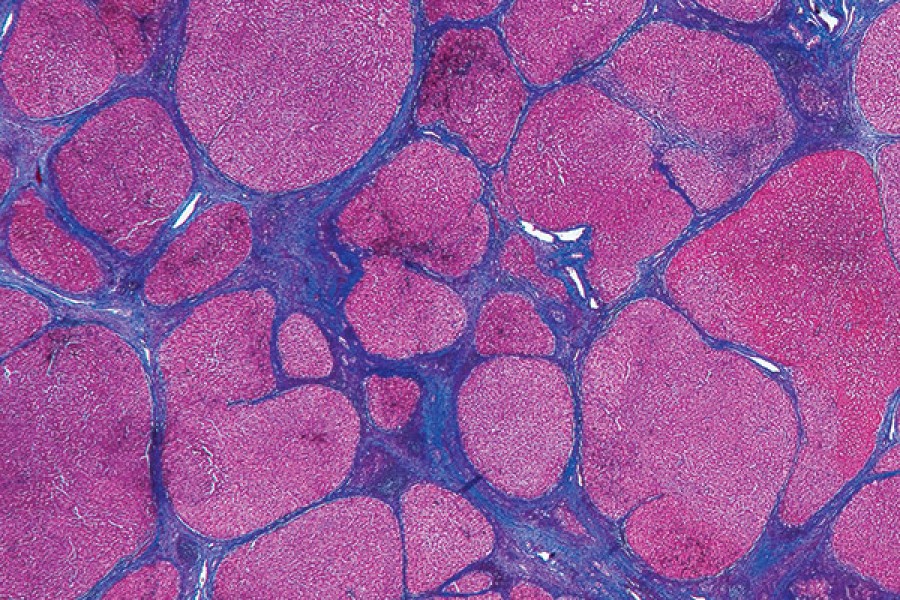

Peering under a microscope at the swirling purple-and-pink-patterned circles, Christine Iacobuzio-Donahue sees an image that could be an abstract painting hanging on a gallery wall.

In truth, the image is of a brain tumor magnified 400 times.

"Sometimes the worse the disease, the prettier it is under the microscope," says Iacobuzio-Donahue, a professor of pathology, oncology, and surgery at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

As a pathologist, Iacobuzio-Donahue was struck by the beauty found in the colors and patterns of the patient specimens she spends her days viewing. Recognizing the need to share this beyond the lab, she partnered with Norman Barker, an associate professor in the departments of Pathology and Art as Applied to Medicine, also in the School of Medicine. Barker, who specializes in microphotography and works with faculty and residents to produce high-quality images, had similar ideas for a medicine-as-art project.

The two—a clinician-scientist and an art photographer—collaborated to collect and curate a gallery of beautiful, rarely seen medical images. The result is their 232-page glossy tome, Hidden Beauty: Exploring the Aesthetics of Medical Science (Schiffer Books, 2012), which serves as an homage to the aesthetics of human disease.

"We are kind of privileged to have a behind-the-scenes tour of the human body that the layperson doesn't necessarily get to see," Barker says.

The book, intended for a broad audience, calls on readers to reconsider pathogens.

"The whole point with art is to make someone think or feel something they haven't before," Iacobuzio-Donahue says. "Diseases are part of the natural world, and they themselves could have elements that are very beautiful. It's hard to see that when you have these preconceived notions about them."

The array of gallstones pictured on the book's cover could be mistaken for a diverse pattern of coral and pebbles mingled with cut crystalline gems. A luminous pattern of black, white, and gold circles is really destroyed lung tissue ravaged by emphysema. What looks like an abstract painting of the ocean against an orange setting sun is actually an electron micrograph of the basic pathogenesis of HIV.

Each visually stunning image is accompanied by text explaining the disease, giving the creative experience an educational benefit.

"We're not condoning disease," Barker says. "It's more of an educational thing to let people know about particular diseases. What does osteoporosis look like? A heart attack? Then this explains the process."

Indeed, the images selected for this book are of diseases and conditions familiar to many. Iacobuzio-Donahue and Barker wanted to display a wide range of pathogens affecting all parts of the body, plus some images depicting normal tissues and the scientific process. They collaborated to collect or create about half the photos, as well as design the book, and the rest of the images were solicited from investigators in and outside Johns Hopkins.

Large versions of the images will be on display as part of a traveling exhibit at various museums around the country, including the Mütter Museum of medical history in Philadelphia.

The project took Barker and Iacobuzio-Donahue nearly four years to complete, as they worked on it outside their day jobs. Their hard work has already started to pay off in positive responses from scientists and artists alike—as well as those who don't spend their days viewing pathogens.

"It's a different view from what they normally get," Barker says, adding that people see the gallstones on the cover, for example, and after realizing what they are viewing, "they want to dig into [the book]."

For Iacobuzio-Donahue, the project has increased her own awareness of the beauty around her. She looks at these images every day, she says, and now it's refreshing to share them with others for the first time. "I am seeing the beauty even more now," she says. "I think it's also encouraging others to look at their own work and research differently."

Posted in Health, Arts+Culture

Tagged art as applied to medicine, norman barker, photography, books