Judith Kunst says that she enjoys living in Remington, a mixed-income neighborhood located just south of the Johns Hopkins Homewood campus. Kuntz moved to Baltimore from Howard County five years ago and was drawn to the urban setting in close proximity to a major university.

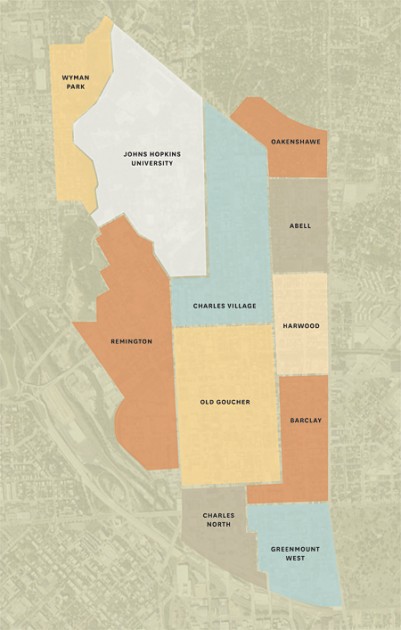

Image caption: The Homewood Community Partners Initiative will focus specifically on 10 neighborhoods and one other entity: Abell, Barclay, Charles North, Charles Village, Greenmount West, Harwood, Oakenshawe, Old Goucher, Remington, and Wyman Park, and the Waverly Main Street district.

Remington, Kunst says, is going through a revival. She points to nearly 30 abandoned houses slated for renovation by 2013, ongoing greening initiatives, and a new artist's studio opening this month on 25th Street.

The area has its shortcomings, however. Particular sore points for Kunst, president of the Greater Remington Improvement Association, are the stretches of 28th and 29th streets that run through Remington, high-traffic areas with unattractive streetscapes and poor lighting that can make the blocks feel unsafe.

She also wouldn't mind having more cafes, restaurants, and art galleries to walk to. A new grocery store and cleaner parks would be nice, too.

Mark Counselman, a lifetime Baltimore resident and president of the Oakenshawe Improvement Association, has a similar wish list.

Turns out, Johns Hopkins does, too.

With a "we agree to agree" attitude in the air, the new Homewood Community Partners Initiative has begun with heaps of optimism.

The ambitious initiative, spearheaded by Johns Hopkins and created last fall, looks to exploit the common areas of self-interest of the university and community residents for the sake of a more vibrant and safer area.

The Homewood Community Partners Initiative, or HCPI, grows out of an understanding that the health and well-being of the Homewood campus are inextricably tied to the physical, social, and economic well-being of its surrounding neighborhoods.

Johns Hopkins has gathered data showing that many students who have been accepted to the university but decline the offer cite the real and perceived conditions of the off-campus experience as a reason for their decision. The recruitment of faculty and staff likewise can suffer from what is viewed as the "HBO version" of Baltimore.

If successful, the HCPI will transform the 10-neighborhood target area into a more vibrant college-town environment with new restaurants and retail stores, an enhanced real estate market, friendly pedestrian walkways, safer streets, improved access to public transportation, better schools, and a variety of amenities.

The initiative will build on existing efforts and create a series of new programs to reach shared goals that can be achieved in both the short and long term.

Some keys to the initiative include the addition in 10 years of 3,000 housing units to help grow the population in Baltimore, a significant reduction in the number of vacant houses and lots, the green-lighting of capital projects to create new retail and commercial corridors, and building on resources that enhance public safety.

University President Ronald J. Daniels—who from the onset of his presidency has said that improving the areas around JHU campuses would become one of his signature initiatives—says that beyond self-interest, the university has intellectual, moral, and ethical obligations to enhance the areas around the Homewood campus.

"I feel quite strongly that the university is a key anchor in the community. We have a long history of positive engagement with the community of which we are part, but now we need to step it up a bit. There is more that we can do," Daniels says. "Baltimore's and the university's fortunes are tied. I can't see a strong and vibrant Johns Hopkins University in a city that is seen as challenged and declining. We have a moral imperative here, and a commitment to the community that needs to be met."

In August 2010, JHU's board of trustees created the External Affairs and Community Engagement Committee—its first new standing committee in 13 years—to identify areas where the university can better engage with its neighbors.

The committee endorsed the Homewood Community Partnership Initiative as its first action. An implementation team—which includes staff from the offices of the President and of Government and Community Affairs, senior officials, and faculty and staff from JHU's schools—was convened to coordinate the initiative.

The HCPI will focus specifically on 10 neighborhoods and one other entity: Abell, Barclay, Charles North, Charles Village, Greenmount West, Harwood, Oakenshawe, Old Goucher, Remington, and Wyman Park, and the Waverly Main Street district.

To date, HCPI leadership has identified five engagement themes: clean and safe neighborhoods; blight elimination and housing creation; public education; commercial and retail development; and local hiring, purchasing, and workforce development.

The university retained Joe McNeely, a nationally recognized consultant from Baltimore with expertise in both community development and university anchor institution programs, to review existing neighborhood plans, work with community leaders and local institutions, review best practices from around the country, and make recommendations in each of the five engagement areas.

McNeely previously worked on Cleveland's successful Greater University Circle initiative, an effort launched in 2005 to stimulate reinvestment and development in a vital urban district located four miles from downtown Cleveland and near Case Western Reserve University.

"The area had a lot of the same dynamic as Johns Hopkins and Baltimore," says McNeely, who is executive director of the Central Baltimore Partnership. "We were able to implement a number of projects that included land banking, the creation of a commercial strip, and pockets of new housing. I see many indicators that we can achieve all this and more here in Baltimore."

To kick off the Homewood Community Partners Initiative, Johns Hopkins hosted in January a workshop that was attended by leaders of both the community and university, including President Daniels.

Throughout the spring and summer, the advisory committee met in working groups and McNeely conducted a series of open meetings for JHU staff, neighborhood associations, the business community, and other stakeholders, including MICA and the University of Baltimore.

This summer, HCPI issued a report, prepared by McNeely, that summarized its findings and offered 30 recommendations.

The overall findings were that the neighborhoods in question have significant challenges in public safety, sanitation, environmental attractiveness, housing blight, quality education, and retail development.

"Mixed in with the good, there are pockets of public safety concerns and areas where people feel a little bit threatened," McNeely says. "The farther away from campus that people get, the more uncomfortable they are with their surroundings." At the same time, McNeely says that these neighborhoods have great strengths and are well-positioned for large-scale development. In particular, he cited the university-owned lot on the corner of 33rd and St. Paul streets and the area just north of Penn Station as two sites for major commercial retail development. "These two areas are ripe for development, without displacing anyone," he says.

Andy Frank, special adviser to President Daniels on economic development, says that the University of Pennsylvania-led urban renewal achieved in West Philadelphia is viewed as the gold standard of what an anchor institution can do. Frank, who will oversee HCPI on behalf of JHU, says that Penn's success in redeveloping a once-blighted area has served as inspiration to other universities across the nation.

"When Joe started the process, there was some apprehension about the degree to which the community's interests would align with Hopkins'. In the end, it turned out that the strategies to improve our students' off-campus experience and attract and retain the best and the brightest faculty involve safer streets, great public schools, vibrant retail, and an array of housing options," Frank says.

The report identified an overall strategy focused on three major shared goals: Create a vibrant urban center, transform the area into a more livable community, and have active, collaborative stakeholders who closely support each other's projects.

To implement these goals, the HCPI recommended a bold set of initiatives.

Examples of crosscutting programs include the creation of a $10 million development fund to finance projects, a land bank to preserve neighborhood stability and foster new strategic development, and a neighborhood improvement fund to provide matching resources for projects initiated and implemented by the community.

To improve quality of life, the report recommends the support of transportation-related efforts such as the proposed Charles Street trolley, a bike boulevard, and more-pedestrian-friendly routes and crossings. It also calls for an arts and culture development marketing campaign.

The initiative seeks to address blight removal and housing creation by partnering with Healthy Neighborhoods Inc. and expanding the university's Live Near Your Work program. Other suggestions included a rental housing conversion program to foster turning rental row houses into owner-occupied units, and actively engaging developers to undertake market-rate projects in the HCPI area.

In the area of education, the initiative will help establish a partnership between the Johns Hopkins School of Education and some public schools in the area—the Margaret Brent Elementary/Middle School and the Barclay School have been identified—and will create more early childhood and after-school programs.

Commercial retail development will occur primarily in the North Charles Street corridor from Homewood south to Penn Station, in addition to Waverly's Main Street and other areas.

McNeely says that the goal is to eliminate the pockets of blighted areas where pedestrians are afraid to travel, in order to better connect communities.

The initiative also looks to support local hiring and purchasing by making institutional commitments to these efforts by Johns Hopkins and other anchors.

To support all the programs, the initiative's leaders hope to raise $60 million from sources that include Johns Hopkins University, city and state funds, foundations, and other area stakeholders. Remington's Kunst, who has attended several HCPI meetings, says that she is very optimistic about the area's future.

"I'm thrilled to death with HCPI," she says. "It is wonderful to see the university so committed to this process and to hear about what can be done."

Counselman, who has lived in Oakenshawe for eight years, says he feels that the area is primed for development. Houses near him have been vacant for too long, and residents are eager to see new amenities.

"We'd love more options in this area, and for students to be able to walk to places like the Waverly Ace Hardware and not feel like they are wandering in the wrong direction," he says. "I think President Daniels should be applauded for his efforts to make this a better community and bring all these parties together. I'm certainly upbeat. We seem to have a lot of wants in common."

President Daniels says that to move the initiative forward, the university will do its part to help find financial resources, partner with city and state officials, and continue to engage actively with area residents. "If we are successful with our efforts, Johns Hopkins will certainly benefit, but so will the residents of this area and their children and families," Daniels says.

Posted in University News

Tagged community, homewood community partners