Being carless may sound like no big deal to lifelong city dwellers, but I come from car people. I'm from Dallas, where car ownership is practically required because everything is "just down the road." In Dallas that typically means at least a 25-minute drive that inevitably involves a highway. Since first coming to Baltimore as a Johns Hopkins undergraduate in 1988, car ownership hasn't made sense. Parking is difficult, car insurance is steep, gas prices go up faster than my wages, and I'm really cheap—I mean, frugal. Surely I can get around without a car.

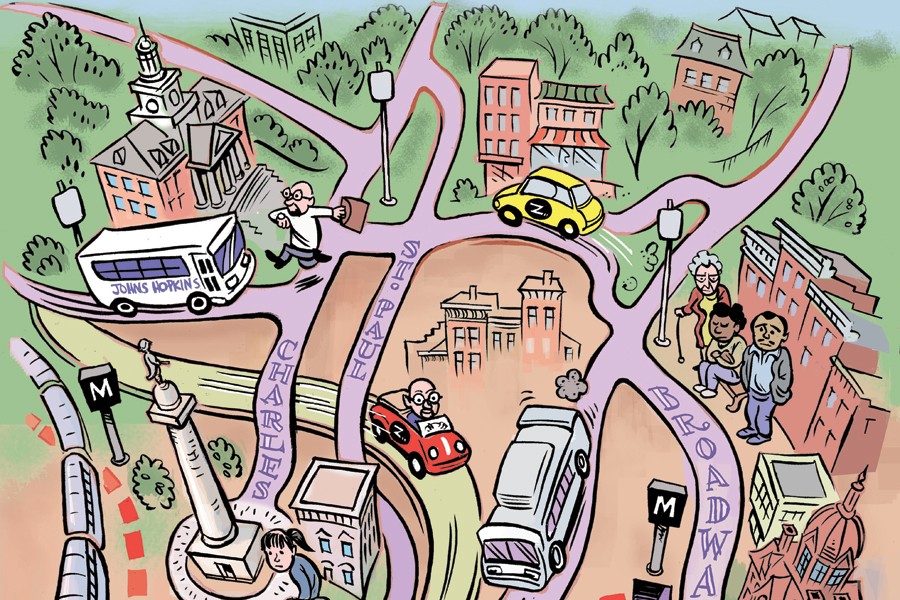

The difference between going carless in Baltimore versus being carless in, say, New York—where a single network of subways and buses serves the entire city—is that you need to be familiar with all the options.

Sometimes the Maryland Transit Administration bus—or light rail or subway—is exactly what you need. Sometimes the free Charm City Circulator is the smart move.

Frequently one of the Johns Hopkins shuttles is perfect for getting around. And sometimes you just have to take a cab or walk. It all depends on point of origin, eventual destination, time of day, and how much time can be allotted for travel.

For example, I work in the Johns Hopkins Office of Communications, and I frequently need to make the nearly five-mile journey from our offices in Fell's Point to the Homewood campus. It takes about 40 minutes to travel between the two by a pair of free shuttles. If I'm running late, a cab ride is about $20 with tip and takes around 20 minutes. If I'm going for a quick meeting, I'll just grab a Zipcar and drive myself, spending less than $12 for an hour's use.

The Homewood-JHMI shuttle is in many ways the most reliable means for getting around, provided travel is bounded by the university's three major local campuses: Homewood in Charles Village, the Peabody Institute in Mount Vernon, and the medical campus in East Baltimore. It's efficient and almost always on time, and Johns Hopkins staff, faculty, and students are preternaturally orderly creatures who have the queue instincts of the English. Its seven stops—Broadway at Monument, Peabody, Penn Station, 27th Street, 29th Street, 33rd Street, and the Interfaith Center at Charles and University—make the trip quite efficient, and rush hours offer express service that bypasses midtown entirely. This route allows riders to get to places near the stops—Hampden, for example, is barely a 20-minute walk from the 29th Street stop—quite dependably.

It runs less frequently on the weekends, though, which is why it's wise to get to know the MTA and Circulator routes, even though Baltimore's public transportation system has earned its imperfect reputation. Each of the MTA's options—bus, light rail, and subway—has its advantages for navigating parts of the city, but the three overlap at only two locations downtown, making connections between lines difficult.

The user experience can be a tad frustrating. The light rail and subway maintain fairly dependable schedules, but buses can run distressingly late. Major lines will be overcrowded during rush hours. During the school year, morning and afternoon buses are often packed with students and, if so, may drive right past people waiting at stops.

That being said, the MTA services the largest area of the city, and with a little planning, it's effective. The light rail is great for catching a movie in Hunt Valley, and the $1.60 fare to the airport is much cheaper than the $25 base-fare cab ride from downtown. Both the No. 8 and No. 48 buses make the trip from 33rd Street to Towson Town Center in the time it takes to read a New Yorker article. The subway reaches the East Baltimore campus in no time at all from downtown, and the Market Place/Shot Tower stop drops riders an easy walk to the Inner Harbor, Harbor East, and Fell's Point.

Since January 2010 the Charm City Circulator, the city's free bus service, offers four routes that loop through downtown Baltimore, with, on average, a 15-minute wait between buses. The east-west Orange line and north-south Purple line efficiently move people from Federal Hill to Penn Station (Purple) and from Hollins Market to Harbor East (Orange). The Green line (which loops from City Hall to The Johns Hopkins Hospital via Harbor East) and the Banner line (which loops from the Inner Harbor to Fort McHenry via Key Highway and Locust Point) offer slightly odd routes, but the Green line provides service to Hopkins Hospital from Fell's Point, and the Banner and Purple lines offer the best options for getting to Federal Hill.

Neither is all that dependable for late-night travel, though, and in all honesty, even as a not-small dude, riding the bus after midnight can be an adventure.

Which is where cabs come in. As in any big city, the quality of the taxi experience depends entirely on the driver. Some Baltimore cab drivers are nice, some aren't. Some know their way around, some don't. Know the city so you can navigate drivers effectively. Recognize that Yellow Cab has a monopoly on pickups at Penn Station, and that an airport service monopolizes pickups from the airport. If you come across a cab driver you like, ask for his card or cell number.

There are times, however, when I need a car—cat litter isn't fun to lug home on the bus—and when those moments arise, I can't recommend Zipcar enough. Joining the car-share service means an annual fee—which is discounted for Johns Hopkins students, faculty, and staff—and a pay-per-use hourly rate for each of its nearly 100 cars in the greater Baltimore area. It's a great, user-friendly way to enjoy the benefits of a car without having to buy a car.

Of course, all of the above is how I've figured out how to navigate Baltimore. The trick isn't to do as I do; it's to get to know the systems and figure out how they work for you. I'm impatient and—as noted—really cheap. Deciding between waiting at least 20 minutes for a bus when I can walk somewhere in 30 minutes is an easy choice for me: I'll walk. It's free—and I can tell myself it's cardio.

But if you happen to see me on the shuttle or waiting for the subway and I look like I'm considering overthrowing the government, I'm not. During my second-ever trip to New York, Joshua Coleman, a JHU classmate who is a Manhattan native, told me to stop looking like a gullible tourist when we were hopping a train to head downtown from the Upper West Side. He grew up in 1970s and 1980s New York. People got mugged. Pockets got picked. You snooze while riding, you lose your stuff. So he taught me how to behave on the subway, how not to look like a mark. And it stuck. So now when I take mass transit, muscle memory takes over, and I put on my subway face.

Posted in University News

Tagged transportation