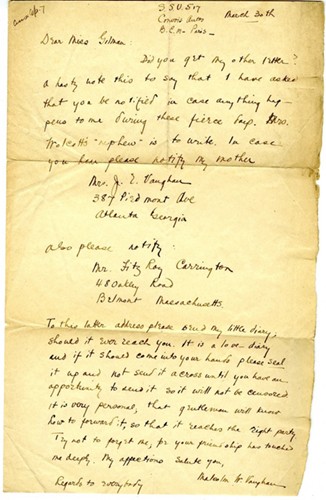

In elegant cursive, a soldier wrote to Elisabeth Gilman, the daughter of Johns Hopkins University's founding president.

He wanted Gilman, who he'd befriended in France during World War I, to notify his mother in Atlanta "in case anything happens to me during these fierce days."

Image caption: Letter from soldier Malcolm W. Vaughan to Elisabeth Gilman

Image credit: The Sheridan Libraries and Museums

The soldier's yellowed letter, now on display in the Milton S. Eisenhower Library at Johns Hopkins University, also contains a private request. He asks that his diary—"a love diary"—be sealed shut and sent to a friend at home. "It is very personal," he wrote. "That gentleman will know how to forward it, so that it reaches the right party."

The American soldier was one of many Gilman came to know as she volunteered her services at a Paris YMCA during World War I. And his letter is among many compelling artifacts from the 1914-1918 conflict that remain in JHU's collections a century later.

In pulling together an exhibition exploring the Hopkins experience of World War I, curators came across not only these types of personal mementos, but also official war memos, photographs, propaganda art, and even medical instruments. Together, the materials—now on display through the Hopkins and the Great War retrospective—offer a look at how the war affected the university and medical communities both at home in Baltimore and abroad.

The retrospective includes visual displays at Homewood, the School of Nursing, and the School of Medicine, in addition to a comprehensive digital exhibition available online. The project marks the first cross-campus exhibition at Johns Hopkins, organized by curators and archivists over the past year.

Related events are also planned, starting with an opening reception tonight at Brody Learning Commons. The event will include a talk from Alice Kelly, from the University of Oxford, on Hopkins nurse Ellen La Motte, who made a controversial name for herself following World War I.

As an American nurse treating soldiers in Europe, La Motte filled up diaries with tales of the graphic horrors she witnessed there—later collecting her accounts into a book, The Backwash of War. Fearing its content aggressively subversive, the U.S. government suppressed the book's publication from 1918 until 1934.

Image caption: An illustration collected by Vashti Bartlett in La Panne, Belgium

Image credit: Alan M. Chesney Medical Archives

La Motte was among hundreds from the Johns Hopkins medical community who worked abroad during the world war.

The Mercy Ship relief expedition, for example, included a large number of surgeons and nurses from Johns Hopkins. The American Red Cross dispatched the ship to Europe in September 1914.

One Hopkins nurse aboard the ship was Vashti Bartlett, who treated soldiers in France and Belgium. Bartlett made a habit of collecting her patients' artwork in a scrapbook, which later landed in the JHU archives. Its images are a mix of amateur cartoons and polished illustrations, revealing soldiers' impressions of warfare, hospital interiors, and the scenery of Europe.

In many cases, the lessons the doctors and nurses took from World War I informed future directions for American medicine.

Serving in the war with the U.S. Army medical corps, Hopkins surgeon John Staige Davis worked with soldiers who were physically disfigured by chemical warfare and shell explosions. When he returned to the U.S., he continued working with veterans dealing with such injuries and became something of an evangelist for the emerging practice of plastic surgery. His 1919 book on the topic is considered a foundational text for its field.

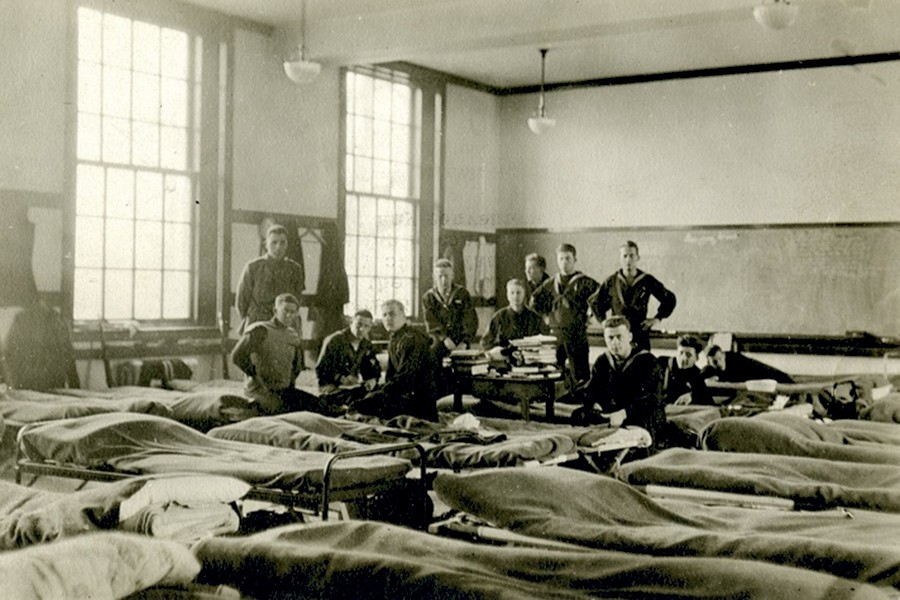

The exhibition also explores impacts felt at home in Baltimore. The Homewood campus, for example, in 1918 became a temporary barracks for soldiers-in-training, as they simultaneously took courses at Hopkins. Photographs on display show young men in cramped, makeshift dormitories in Gilman Hall and other buildings.

Though Johns Hopkins was prepared to accept more than 700 of these trainees, the program lasted only two months—World War I ended in November 1918, and the young men who were lucky enough to have not been deployed returned home.

About the exhibit

Hopkins and the Great War exhibits are on display in the following locations:

- The Milton S. Eisenhower Library on the Homewood campus, on both the M and Q levels

- The Anne M. Pinkard Building of the School of Nursing

- The William H. Welch Medical Library at the School of Medicine (available starting Sept. 22)

In addition to tonight's opening ceremony on the Homewood campus, events include:

- Ready to Serve: A Story of Hopkins Nurses in WWI: A performance by Ellouise Schoettler based on personal letters of nurses who served at Hopkins Base Hospital 18. The event will take place in the School of Nursing's Alumni Auditorium from 1 to 2:30 p.m. on Sept. 23.

- Dispatches from the Second Battlefield: Four Hopkins Nurses Tell Their World War I Stories: The official opening reception for the Nursing and Medical exhibits will featuring a talk by University of Maryland professor Marian Moser Jones. The event will take place in the William H. Welch Medical Library at 4:30 p.m. on Oct. 18.

More details, and the full online exhibit, are available on the Hopkins and the Great War retrospective site.

Posted in Arts+Culture, University News

Tagged history, sheridan libraries, archives, hopkins retrospective, world war i