The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies will co-lead a $15.4 million effort to develop new systems for quickly screening libraries of drugs for potential effectiveness against schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, the National Institute of Mental Health announced today.

The consortium, which includes four academic or nonprofit institutions and two industry partners, will be led by Hongjun Song of Johns Hopkins and Rusty Gage of Salk.

Bipolar disorder affects more than five million Americans, and treatments often help only the depressive swings or the opposing manic swings, not both. And though schizophrenia is a devastating disease that affects about three million Americans and many more worldwide, scientists still know very little about its underlying causes—which cells in the brain are affected and how. Existing treatments target symptoms only.

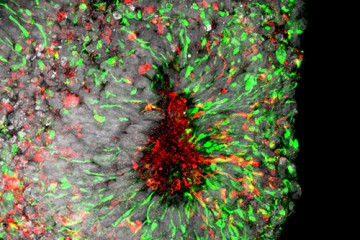

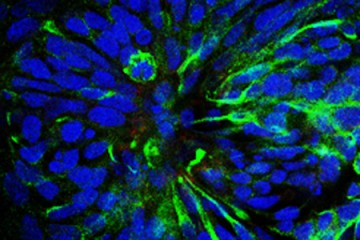

With the recent advance of induced pluripotent stem cell, or iPSC, technology, researchers are able to use donated cells, such as skin cells, from a patient and convert them into any other cell type, such as neurons. Generating human neurons in a dish that are genetically similar to those of patients offers researchers a potent tool for studying these diseases and developing much-needed new therapies.

A major aim of this collaboration is to improve the quality of iPSC technology, which has been limited in the past by a lack of standards in the field and inconsistent practices among different laboratories.

"There has been a bottleneck in stem cell research," says Song, a professor of neurology and neuroscience at Johns Hopkins. "Every lab uses different protocols and cells from different patients, so it's really hard to compare results. This collaboration gathers the resources needed to create robust, reproducible tests that can be used to develop new drugs for mental health disorders."

Adds Gage, professor of genetics at Salk: "IPSCs are a powerful platform for studying the underlying mechanisms of disease. Collaborations that bring together academic and industry partners, such as this one enabled by NIMH, will greatly facilitate the improvement of iPSC approaches for high-throughput diagnostic and drug discovery."

Also see

The teams will use iPSCs generated from more than 50 patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder so that a wide range of genetic differences is taken into account. By coaxing iPSCs to become four different types of brain cells, the teams will be able to see which types are most affected by specific genetic differences and when those effects may occur during development.

First the researchers must figure out, at the cellular level, what features characterize a given illness in a given brain cell type. To do that, they will assess the cells' shapes, connections, energy use, division, and other properties. They will then develop a way of measuring those characteristics on a large scale, such as recording the activity of cells under hundreds of different conditions simultaneously.

Once a reliable, scalable, and reproducible test system has been developed, the industry partners will have the opportunity to use it to identify or develop drugs that might combat mental illness.

"This exciting new research has great potential to expedite drug discovery by using human cells from individuals who suffer from these devastating illnesses," says Husseini K. Manji, global therapeutic area head of neuroscience for Janssen Research and Development. "Starting with a deeper understanding of each disorder should enable the biopharmaceutical industry to design drug discovery strategies that are focused on molecular pathology."

The researchers also expect to develop a large body of data that will shed light on the molecular and genetic differences between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. And, since other mental health disorders share some of the genetic variations found in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, the data will likely inform the study of many illnesses.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged neuroscience, mental health, stem cells, bipolar disorder, hongjun song, schizophrenia