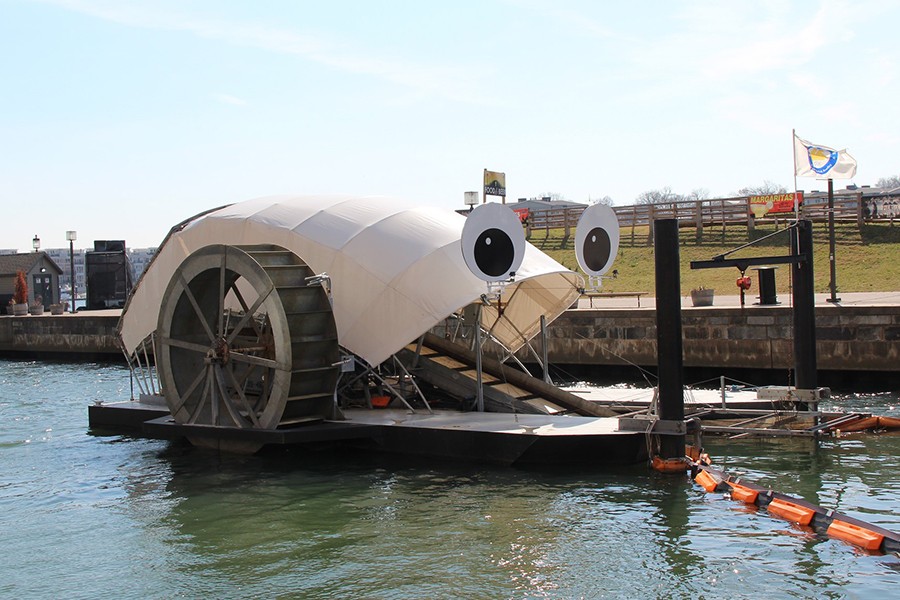

Two Johns Hopkins University students decided to take on a persistent problem facing Baltimore after finding inspiration in an unlikely source: an anthropomorphized, googly-eyed harbor trash collector dubbed "Mr. Trash Wheel."

Chris Kelley, a PhD candidate studying geography and environmental engineering at JHU's Whiting School of Engineering, and Ramya Ambikapathi, a PhD candidate studying human nutrition at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, say they have grown accustomed to seeing litter on the city's streets. But when they realized how much trash winds up in Baltimore's Inner Harbor, they decided to tackle litter as a public policy problem.

Image caption: Chris Kelley (left) and Ramya Ambikapathi (right)

Their research caught the attention of the Abell Foundation, which recognized Kelley and Ambikapathi with the Abell Award in Urban Policy. The award goes to the student or students from area colleges who author the most compelling papers analyzing a serious policy problem facing Baltimore City and proposing feasible solutions. The award is accompanied by a $5,000 prize.

Johns Hopkins University students have won the Abell Award 12 times since 2003.

In their work, Kelley and Ambikapathi cite data from a report on Mr. Trash Wheel—a cleanup initiative that filters trash out of the harbor using a water wheel—showing that since the project began in May 2014, the wheel has recovered at least 218,720 plastic bottles, 280,619 polystyrene "clamshell" containers used to package food, 137,570 grocery bags, 202,139 snack bags, and more than 7 million cigarette butts.

"After learning how much litter ... is food and drink packaging, we decided to examine how littering occurrences are spatially related," Kelley says.

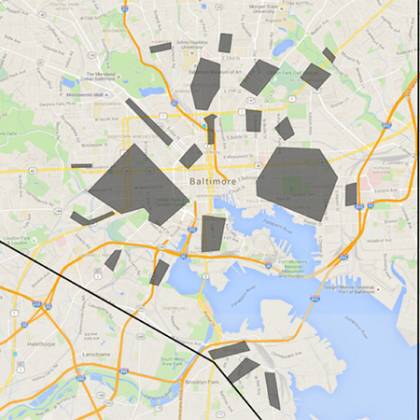

Image caption: From their analysis, Chris Kelley and Ramya Ambikapathi posit the highlighted areas of Baltimore as potential “litter hot spots”

Image credit: Christopher Kelley and Ramya Ambikapathi

The team created maps using spatial analysis, surveys, personal observations, and interviews to pinpoint areas of the city with high concentrations of litter. They discovered that locations near carry-out restaurants, convenience stores, bus stops, public middle and high schools, and food desert regions tended to accumulate the most trash. A significant portion of litter is generated when people consume food outside the home, they found.

"This is an environmental issue with an important social component," Kelley says. "If you, like a large proportion of Baltimoreans, live in area without a nearby grocery store, your readily available food choices may come with lots of packaging."

And yet, the team notes, the city does not position trash receptacles accordingly.

"If the city assumes that all neighborhoods produce trash at roughly the same per capita rate, then neighborhoods without ready access to grocery stores would likely produce more litter than other neighborhoods," Kelley says. "This is a subtle but important point that is, unfortunately, easy to overlook."

The team emphasizes that their research relies on approximations, including the availability of public trash cans on streets, which they extrapolated by counting trash receptacles located along high-traffic corridors in the city such as Broadway, North Avenue, and Fayette Street.

"There are some key assumptions we had to make along the way," Kelley says. "Like using reports of litter filed through the Baltimore 311 system rather than tracking litter ourselves, and approximating the distances that pieces of food packaging litter might travel due to rain or wind."

The team followed their data mapping and analysis with policy suggestions. They propose that the Department of Public Works conduct an inventory of public trash cans so that the city can review the distances between existing cans and add additional cans where needed to reduce the likelihood of people dropping litter onto the ground. In their paper, they call this the "Disneyland Theory," based on a study reportedly commissioned by the Disney corporation for its theme parks that determined that the average distance a person will walk to a trash can before littering is roughly 30 steps.

Other suggestions include topping existing trash cans with narrow-mouthed lids, which reduce the likelihood of dumping; marking each trash can with a clear identifier to help pedestrians report overflowing trash cans that need emptying; and using social media reporting and hashtags for citizens to report litter and overflowing trash cans.

Posted in Health, Politics+Society, Community

Tagged community, baltimore, urban planning, environmental health, public policy