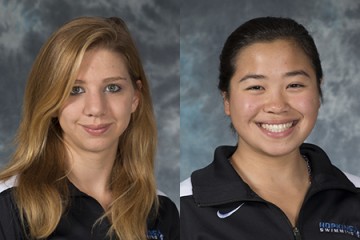

Image caption: North Korean gymnast Hong Un-jong (left) poses with South Korean gymnast Lee Eun-ju (right)

Not for the first time, a selfie made waves on social media last week.

This time, the speculation was directed toward a North Korean gymnast, Hong Un-jong, who posed for a snap alongside a South Korean gymnast at the Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro. A tweet about the photo was shared more than 18,000 times. As the photo spread online, commenters wondered whether Hong would be able to safely return to her home country after what some perceived as "fraternizing with an enemy."

It's not a new line of criticism leveled against the totalitarian government and its athletes, but it may be an inaccurate one, argues Michael Madden in a recent article for BBC News. In response to the flurry of tweets and comments, Madden—a visiting scholar at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies U.S. Korea Institute and a frequent contributor to 38 North—explains what life is typically like for North Korea's star athletes.

"For athletes from the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), [competing at the Olympics] is an opportunity to represent the country in front of an international audience in spite of the intense pressure of expectations from home," says Madden.

"Sports diplomacy" has been a national policy in North Korea since the 1980s, he adds, and has been championed by leader Kim Jong-Un with renewed interest in recent years. Successful athletes receive state titles and government awards, such as documentary films, feature films, and state-granted fully furnished apartments.

Athletes are unlikely to be punished for their interacting with fellow athletes, but Madden notes that failure to win an Olympic event could result in repercussions. Rumors that failed athletes would face labor camps or executions are decades old, but Madden explains that most likely, athletes endure so-called "criticism sessions" conducted by the party or the military.

"During the session, members of a small party group critique one's performance, with several people upbraiding the individual for their substantive performance (or lack thereof) and their perceived ideological failures," Madden writes. "At the end, the person being critiqued then engages in self-criticism and resolves to do better in the future."

But, Madden adds, "the worst that usually happens to athletes who fail to place or win at competitions is that North Korean state media doesn't mention them."

Read more from BBC NewsPosted in Athletics, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged north korea, olympics