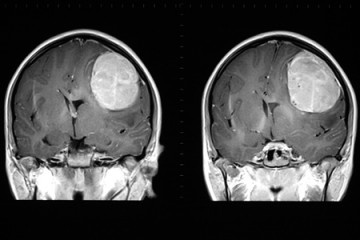

An experimental lab test developed at Johns Hopkins could help predict how quickly a patient's brain cancer will spread.

Using a small glass "cell racetrack," researchers were able to accurately clock the speed of brain tumor cell movement. A report on their findings is published online in Cell Reports.

Video credit: Johns Hopkins Medicine

Researchers tested the cells of 14 patients with glioblastoma, an aggressive cancer of the glial cells in the brain that is known to resist surgery and other treatment.

"After I remove a brain tumor from a patient, the patient always asks me, 'Doc, how long do I have?' I don't have a reliable way to answer them," says Alfredo Quinones-Hinojosa, professor of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine and director of the Brain Tumor Surgery Program. "But we have taken a step to creating a possible way to provide useful updates, inform treatment choices, and perhaps develop new treatments faster."

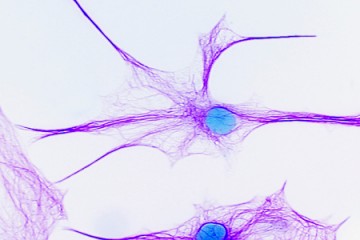

Using their "cell racetrack"—a glass slide with tiny plastic ridges down its length—the scientists were able to visualize which cancer cells were moving most quickly, mimicking the initial migration that leads to brain cancer invasion. Results of several experiments suggested that tumors with the fastest cells paralleled the clinical outcomes of the 14 glioblastoma patients at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Quinones-Hinojosa says.

The cell racetracks, described in an earlier 2012 study, contain ridges designed to simulate the surface of the brain, where migrating cancer cells travel along grooves of white matter and blood vessels.

For this round of experiments, scientists first identified a chemical way to get the cells moving along the slide, using a platelet-derived growth factor, or PDGF. They soon found that PDGF strongly affected the faster cells.

Quinones-Hinojosa says the researchers paid specific attention to those faster cells, "because these are the really bad cells that we believe are going to cause the tumor to spread."

To see if their test might help predict the most aggressive brain tumors, the scientists compared the PDGF-primed cells from the glioblastoma patients with clinical data from those patients. The team found that five patients with the fastest tumor cells had recurrence of their cancers within six months. The six patients with slower tumor cells had no recurrence between six and 22 months.

The research could be significant for improving predictions of how quickly and lethally brain cancer will spread, the researchers say. Currently, the technologies available to predict treatment responses—genetic- or protein-based tests—fail to predict cell migration rates and survival times.

Read more from Hopkins MedicinePosted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged cancer, brain cancer, alfredo quiñones-hinojosa