Image caption: Charles E. Connor

People are intuitive physicists, knowing from birth how objects under the influence of gravity are likely to fall, topple, or roll. In a new study, scientists have found the brain cells apparently responsible for this innate wisdom.

In a part of the brain responsible for recognizing color, texture, and shape, Johns Hopkins University researchers found neurons that used large-scale environmental cues to infer the direction of gravity. The findings, published online in the journal Current Biology, suggest these cells help humans orient themselves and predict how objects will behave.

"Gravity is a strong, ubiquitous force in our world," said senior author Charles E. Connor, a professor of neuroscience and director of the university's Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute. "Our results show how the direction of gravity can be derived from visual cues, providing critical information about object physics as well as additional cues for maintaining posture and balance."

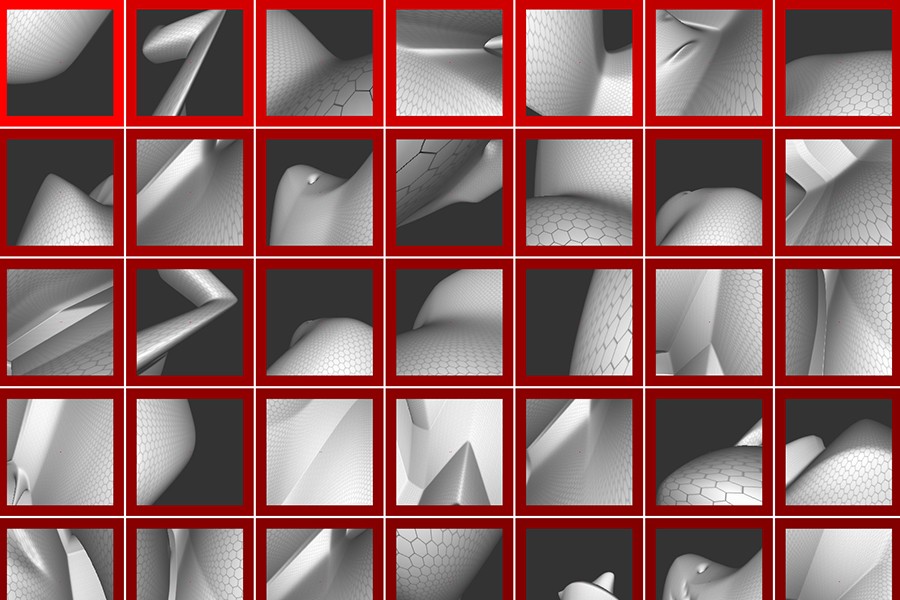

Connor, along with lead author Siavash Vaziri, a former Johns Hopkins postdoctoral fellow, studied individual cells in the object area of the rhesus monkey brain, a remarkably close model for the organization and function of human vision. They measured responses of each cell to about 500 abstract three-dimensional shapes presented on a computer monitor. The shapes ranged from small objects to large landscapes and interiors.

They found that a given cell would respond to many different stimuli, especially large planes and sharp, extended edges. What tied these stimuli together was their alignment in the same tilted reference frame. These cells, sensitive to different tilts, could provide a continuous signal for the direction of gravity, even as a person constantly moves.

In other words, Connor said, these neurons could help people understand which way is up, even while they move.

"The world does not appear to rotate when the head tilts left or right or gaze tilts up or down, even though the visual image changes dramatically," he said. "That perceptual stability must depend on signals like these that provide a constant sense of how the visual environment is oriented."

The researchers' initial discovery of cells sensitive to large-scale shape, reported in Neuron in 2014, was surprising because they found them in a brain region long regarded as dedicated exclusively to object vision. The new findings make sense of this anatomical juxtaposition, since knowing the gravitational reference frame is critical for predicting how objects will behave.

"When we dive after a ball in tennis, the whole visual world tilts, but we maintain our sense of how the ball will fall and how to aim our next shot," Connor said. "The visual cortex generates an incredibly rich understanding of object structure, materials, strength, elasticity, balance, and movement potential. These are the things that make us such expert intuitive physicists."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged brain science, neuroscience, vision