A year ago, only a true idealist could have imagined that more than 180 countries could reach a watertight agreement to address global warming, Todd D. Stern, the U.S. State Department's special envoy for climate change, said Thursday during a talk at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

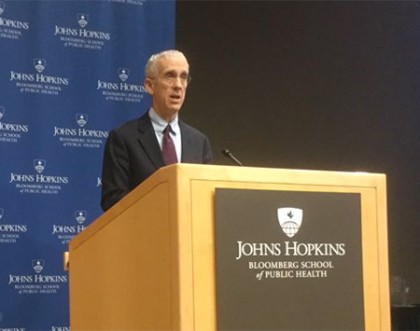

Image caption: Todd Stern, special envoy for climate change at the U.S. State Department, speaks at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

But that's exactly what happened last month in Paris at the United Nations Climate Change Conference. The landmark agreement negotiated there, which demanded accountability and benchmarks of progress in a quest to limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, "went north of what we thought was a best-case scenario," Stern said.

Johns Hopkins professors and policy experts gathered Thursday to discuss the ripple effects of the Paris Agreement on climate change at a Centennial Policy Scholar seminar series event. Stern was a particularly relevant guest—he acted as "the face of America in these negotiations," said former U.S. Congressman Henry Waxman, Centennial Policy Scholar at the Bloomberg School and host of the seminar.

The State Department official repeatedly focused on the Paris Agreement as a door-opener. That so many countries came together for the agreement "sends a powerful signal to players around the world," he said.

Adam Sheingate, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins, asked how partisan divides in Congress might impede progress. Stern acknowledged that "in the long run, we will need congressional action" to bring forward new legislation related to climate change, but he also noted that many terms of the Paris Agreement do not require congressional consent. Both he and Waxman emphasized that the president has the ability to enact new environmental policies based on executive powers embedded in pre-existing laws, such as the Clean Air Act. President Obama, Stern said, has been "enormously aggressive and enormously effective" in this regard.

Vicente Navarro, professor of health and public policy at Johns Hopkins, likened the United States' need for progress on climate change to its slow-to-budge but ultimately decisive attitude shifts toward tobacco. "We have to develop an anti-CO2 culture," he said. "That is the great challenge."

Stern noted the significance of the collaboration between U.S. and China going into the Paris negotiations, a symbolic partnership that "sent very positive shockwaves through the climate negotiating world," he said.

Just as important, he said, was diverging from old patterns that sharply separated developed countries from developing countries, particularly on the subject of transparency requirements. At one point during the Paris negotiations, Stern said, it was suggested that the details of such requirements be worked out at a later date. But leaders were successful in rejecting that idea.

"We knew this was the moment," he said, "this was when the spotlight was on."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged climate change, global warming