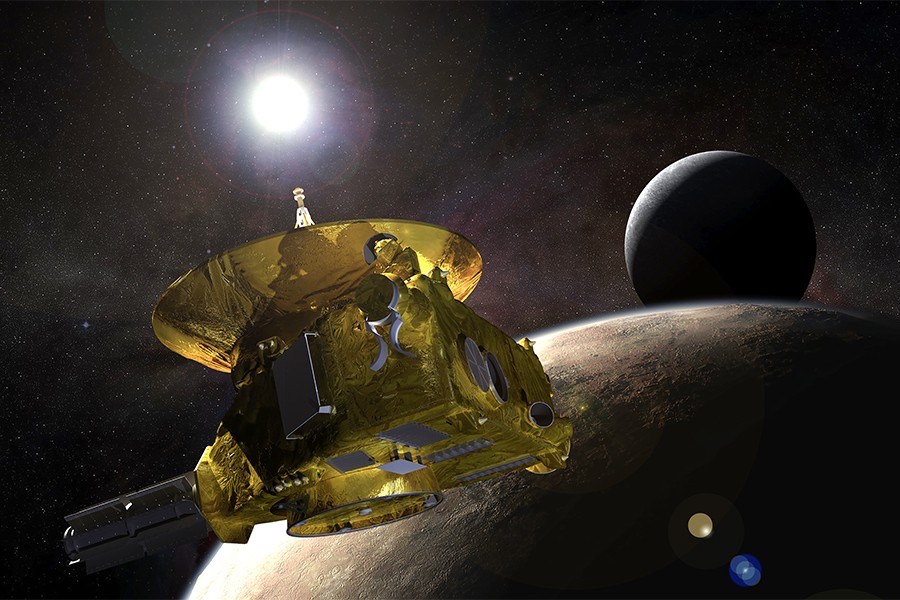

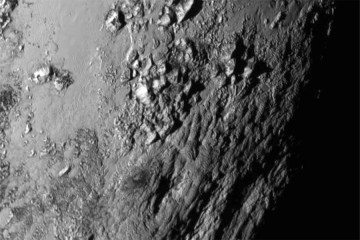

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft has zipped by Pluto and continues on its voyage beyond our solar system and deeper into the Kuiper Belt. By now, we've all seen the stunning high-resolution images of the dwarf planet's icy surface captured by the craft's Long Range Reconnaissance Imager, or LORRI.

LORRI, however, is just one of seven instruments that make up New Horizons' science payload, which collected a treasure trove of data during the flyby that brought the craft within 7,800 miles of Pluto. In some sense, the surface images are just an appetizer for a full course of scientific data headed our way.

New Horizons' instruments will tell us more about the composition and structure of Pluto's dynamic atmosphere, the geology of the planet's surface, interactions between Pluto and the solar winds, the materials that escape the planet's atmosphere, and dust grains produced by collisions of asteroids and other Kuiper Belt objects.

New Horizons collected so much data—stored on a pair of 32-Gbit hard drives—that it will take 16 months to send it all back to Earth. And you thought the streaming speed on that True Detective episode was slow.

But just how does all the information get back to us, and why will it take so long?

For one, consider that the information has to travel more than three billion miles. Even moving at the speed of light, that's a 4.5-hour trip for a single image.

Then there's the data rate challenge, says the Applied Physics Laboratory's Chris DeBoy, the lead RF (wireless and high-frequency signals) communications engineer for the New Horizons mission to Pluto. As an instrument makes an observation, data is transferred to a solid-state recorder—similar to a flash memory card for a digital camera—where it's compressed, reformatted, and transmitted to Earth through the spacecraft's radio telecommunications system, a 2.1-meter high-gain antenna. The antenna, however, has an output power of 12 watts and receives a signal from Earth that is approximately a millionth of a billionth of a watt. Taking into account the distance and low-powered signal, the New Horizons "downlink" rate is considerably low, especially when compared to rates now common for high-speed Internet, which can move information faster than 100 Mbps. New Horizons currently can only move data at a rate of 1 to 2 Kbps.

"To cover that vast distance severely limits the data rate," DeBoy says.

The New Horizons spacecraft, just like Earth-bound computers, speaks in a stream of cryptic-looking 1s and 0s that traverse space via these low-frequency radio waves. The signal is so weak that large antenna dishes on Earth, part of NASA's Deep Space Network, are required to receive the faint radio waves.

"The encoded 1s and 0s that travel billions of miles are so small that the signal spreads, and it's a whisper by the time it gets back to Earth," DeBoy says. "But the DSN system can tease out that whisper, so we can receive the information on the ground."

Data received on Earth through the Deep Space Network is sent to the New Horizons Mission Operations Center at APL, where data are "unpacked" and stored. The data is cleaned up—bad data is removed—and put into large daily archive files. At this point, the data is intact, but it is in a very raw form. The Science Operations Center at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, sorts this out and produces usable science data. The packets of bits need to be decoded and pieced together to make each data set or image.

DeBoy says that the images already received from New Horizons were prioritized and encoded in special transmission turbo code. Likewise, the remaining data sets will be prioritized and sent piecemeal, not in one huge data dump. New data will arrive continuously, DeBoy says, and slowly be unveiled over the next 16 months.

It's an exciting time for the mission, DeBoy says, even though New Horizons has already passed Pluto and made history.

"It was a great moment when we saw the signal come back and knew that the spacecraft had survived," he says. "Now it's our job to get the data that will be trickling back to us. There are lots of new discoveries to come."

An earlier version of this article misstated the size of the hard drives on which New Horizons stores data.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory, space exploration, nasa, new horizons