CONAKRY, Guinea—Dr. Thierno Souleymane Diallo is a formidable ally in Guinea's race to prevent and contain the spread of the deadly Ebola virus among women and families. As a survivor of the disease, he is championing with colleagues the infection prevention and control skills that can save lives.

Image credit: Jhpiego/Jacqueline Aribot

Thierno was infected with the virus during his rotation in the maternity ward at the National Hospital Ignace Deen last August. The 35-year-old father of three was treating a pregnant patient who showed no Ebola-related symptoms, but who later tested positive for the disease. The doctor candidly admits that he could have avoided infection if he had known "to take every precaution."

However, at the time, the hospital was not following recommended infection prevention and control practices.

"I washed my hands between each treatment act with the woman, but five team members, including me, had to be isolated because of our contact," Thierno said. "I was the only one of the team to develop the disease."

He spent 21 days in an Ebola treatment center.

"Sometimes I prayed to God to let me sleep, to forget my state ... and when I woke up, I felt like my entire body was full of lead," he said of his terrifying battle against the Ebola virus.

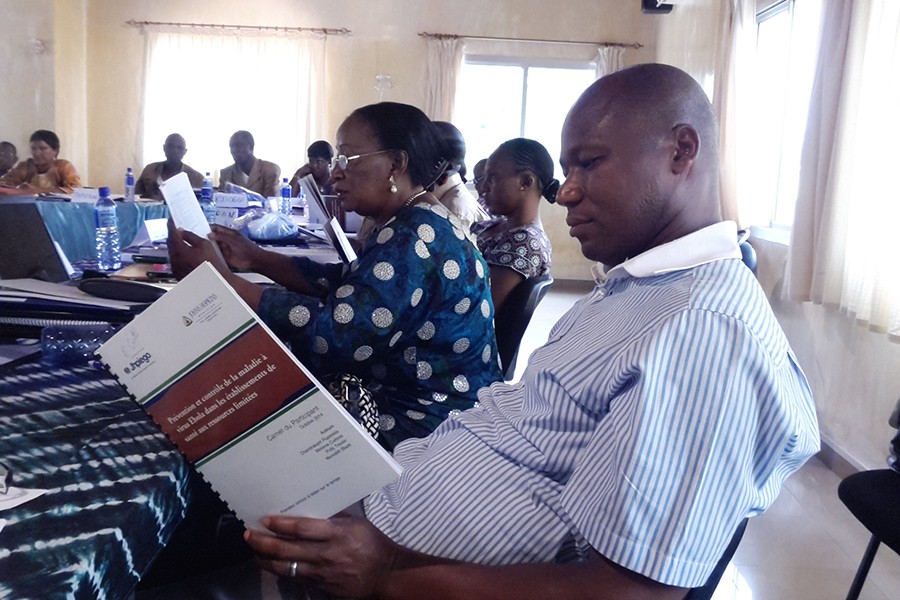

Upon his release from the treatment center, Thierno spent another two and a half months recovering at home because of joint pain. After returning to work, he participated in an infection prevention and control update and refresher training for health workers during which he learned the importance of following proper protocols, especially during the Ebola outbreak. The five-day training was organized by the U.S. Agency for International Development's Maternal and Child Survival Program, which is led by Jhpiego—an international nonprofit health organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University—in conjunction with the Ministry of Health in Guinea. The training used lectures along with simulated practical sessions and site visits to health facilities to allow for hands-on demonstrations of proper infection prevention and control to protect providers and their patients.

Thierno is now among 27 providers with updated skills who are managing a large-scale training, under the guidance of the Maternal and Child Survival Program team, for 2,200 Guinean health care workers in infection prevention and control practices adapted for Ebola-impacted countries. Nearly 1,000 have been trained so far.

Thierno and the other trainers are also providing follow-up supportive supervision every two weeks as part of the Ministry of Health's concerted efforts to keep frontline health workers safe and prepared to serve Guineans who may become ill. As survivors, they are thought to be immune to the virus but nevertheless are implementing nfection prevention and control procedures fully.

On some days, Thierno recalls, he was so disoriented that he did not even recognize his wife when she came to see him in the designated visitors' area of the Ebola treatment center. During this time, the doctor suffered from bloody diarrhea, nausea, indescribable body aches, and constant 104-degree fevers that lasted for long periods of time.

When Thierno was discharged from the treatment center, only his wife, children, and mother would approach him.

"Others maintained a distance, some even shrank from my sight and did not want to shake my hand or have any contact at all," he said.

But when he was finally able to return to work, he said, "I had no problems. My colleagues accepted me."

Thierno believes that the main reasons he contracted the disease were that he, like other providers at the facility, used only one glove on one hand during patient treatment in the maternity ward and that the solution of chlorine prepared for disinfection was not the proper concentration. In subsequent trainings at his facility, Thierno has reinforced to colleagues that one glove is not an acceptable practice.

The survivors offer valuable insight to providers they train about why such infection prevention and control measures are critically important. Their stories also highlight the importance of seeking care immediately if a case of Ebola is suspected—the survival is higher for those who initiate care with the first sign of symptoms, as Thierno did.

"This Jhpiego training will influence me to make positive behavior changes and raise my awareness of IPC practices that we neglected," Thierno said. "... This training has closed the door on ignorance related to infection prevention and opened a door on behavior change."

Rachel Waxman contributed to this article.

Posted in Health

Tagged global health, jhpiego, infectious disease, ebola