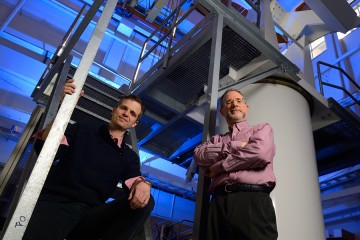

Marc Kamionkowski, a Johns Hopkins professor who is developing theories to explain how the universe was formed, is one of six physicists who have been selected to receive a 2014 Simons Foundation Investigator award, which will provide up to $1 million to support his work.

Image caption: Marc Kamionkowski

The Simons Investigator program gives each recipient $100,000 annually in research funding for five years. The support may be extended for an additional five years, after an evaluation of the scientific impact of the scholar's work.

This program was launched in 2012 to provide stable support to outstanding scientists, enabling them to conduct long-term studies of fundamental questions. The awards are given to mathematicians, theoretical computer scientists, and to theoretical physicists such as Kamionkowski.

"The intent is to support theoretical physicists to think freely and creatively, and that's a great thing," said Kamionkowski, who joined the university's Department of Physics and Astronomy in 2011. "What I do is pure curiosity-driven research. This award is a huge honor for me."

Said Daniel H. Reich, chair of the Department of Physics and Astronomy: "Dr. Kamionkowski is one of the leading theoretical cosmologists of his generation. His work is helping to guide the study of the earliest moments of the universe. This award from the Simons Foundation is a fitting recognition of his accomplishments, and we are very excited to see where his research that will be enabled by the Simons Investigatorship will take us."

Cosmologists, Kamionkowski said, try to figure out where the universe came from. Other space researchers use powerful telescopes and other instruments to gather data about stars and other distant phenomena. "Our job as theorists," he said, "is to study a lot of these measurements and try to see what they're trying to tell us. We then attempt to come up with a consistent history of the universe that conforms to the laws of physics.

"We spend a lot of time sitting around brainstorming," he added. "Sometimes we come up with brilliant ideas, only to find out a few days later that they were ridiculous. But sometimes we come up with ideas that are then used to guide observations that may result in important discoveries."

Earlier this year, in fact, a team of observational cosmologists found evidence that appears to support the idea of cosmic inflation—a period of very rapid expansion that is believed to have happened in a fraction of a second after the Big Bang.

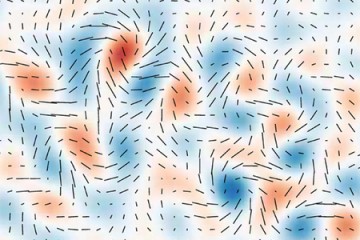

Using a telescope located at the South Pole, researchers may have detected a distinctive pattern of light in the sky. This pattern, a lingering "glow" dating back to the birth of the universe, was predicted 18 years ago by Kamionkowski. Tiny fluctuations in this afterglow are believed to provide important clues to conditions in the early universe. The South Pole findings are still being reviewed, Kamionkowski said.

"The evidence is tantalizing, but not yet fully conclusive," he said. "I'm looking forward to seeing some of the remaining questions resolved by several forthcoming experiments, including the CLASS telescope project that is co-led by Chuck Bennett and Toby Marriage, two of my department colleagues at Johns Hopkins."

His theories concerning cosmic microwave background radiation—that faint glow remaining from the Big Bang—also tie in with recent efforts aimed at mapping the universe.

"Our job as cosmologists is to figure out what this map is revealing to us," he said. "There's a huge amount of information there, if we can just crack the code. It's helping us to construct a model detailing exactly what happened in that fraction of a second after the Big Bang occurred."

He added, "One of the things that has unified people over so many generations is that they've looked up at the sky and wondered about the nature of the universe. What we're doing here has been part of the human endeavor for a very long time."

Beyond his scholarly pursuits, Kamionkowski has developed an outstanding record as a mentor to students and postdoctoral fellows. Of the 38 he has supervised, all but five continue to work in science-related careers, focusing on topics such as particle and nuclear physics; physical and early-universe cosmology; and stellar, high-energy, and gravitational-wave astrophysics.

Funding from the Simons Investigator award, Kamionkowski said, will allow him to add a postdoctoral fellow or two graduate students to his current research team. It will also enable team members to travel to important science conferences and to invite prominent scientists from other institutions to visit Johns Hopkins.

A native of Cleveland, Kamionkowski received a BA from Washington University in St. Louis in 1987 and a PhD from the University of Chicago in 1991. After three years of postdoctoral study at the Institute for Advanced Study, he joined the faculty of Columbia University in 1994 as an assistant professor of physics. In 1999, he became a member of the faculty of Cal Tech as a physics professor, eventually servings as the school's Robinson Professor of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics from 2006 to 2011.

Kamionkowski is a member of the American Astronomical Society, American Physical Society, American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the International Society for General Relativity and Gravitation. He has been awarded an SSC National Fellowship, an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship, a DoE Outstanding Junior Investigator Award, the Helen B. Warner Prize of the American Astronomical Society and the DoE's E. O. Lawrence Award for Physics. He was elected a Fellow of the American Physical Society in 2008 and to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2013.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged cosmology, astrophysics, space, marc kamionkowski