Beginning in 1995, in a genetics lab at the University of Pennsylvania, Haig Kazazian and his colleague Arupa Ganguly tested roughly 500 women per year for the breast-cancer-predicting genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, whose mutations are linked to increased hereditary risk for breast and ovarian cancer.

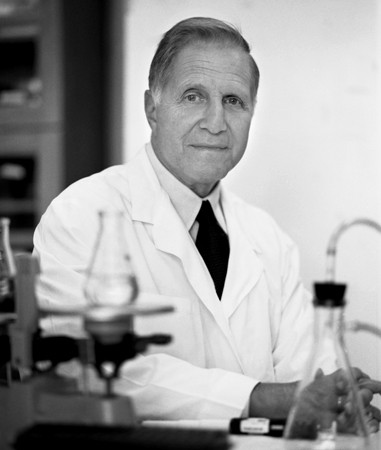

Image caption: Haig Kazazian

Image credit: Johns Hopkins University

In 1999, they received a cease and desist letter from Myriad Genetics Inc., which had successfully patented the genes in 1998. In 2008, Kazazian&mash;a 1962 Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine graduate and a professor in the school's Institute of Genetic Medicine—and Ganguly became the first plaintiffs in the ACLU's case against Myriad and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Lower courts approved Myriad's patents, but today, in a unanimous ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down patents held by Myriad Genetics on BRCA1 and BRCA2. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that the DNA is a product of nature and not eligible for a patent merely because it has been isolated.

Read the decision in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc. on the Supreme Court's official blog.

More, from The Washington Post:

The Supreme Court ruled Thursday that companies cannot patent parts of naturally-occurring human genes, a decision with the potential to profoundly affect the emerging and lucrative medical and biotechnology industries.

The high court's unanimous judgment reverses three decades of patent awards by government officials. It throws out patents held by Myriad Genetics Inc. on an increasingly popular breast cancer test brought into the public eye recently by actress Angelina Jolie's revelation that she had a double mastectomy because of one of the genes involved in this case.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged genetics, biomedical engineering, biotechnology