Editor's note: This profile of Richard Ben Cramer '71 was originally published by Johns Hopkins Magazine in November of 1992, the same year that What It Takes: The Way to the White House was released.

Finally, after six years and thousands of interviews, it had come down to one last phone call. It was D-Day, it was get-the-book-to-the-publisher-or-this-all-becomes-an-academic-exercise day, and Richard Ben Cramer was still on the phone.

This was last April, and Cramer's book in progress, What It Takes: The Way to the White House, was about the candidates in the 1988 presidential campaign. If it didn't come out before the fall election, forget it. Who would want to read it? It would be ancient history.

At this point, the manuscript was 18 months late. The book was supposed to have been published a year before. Now editors at Random House were editing like a daily newspaper, a chunk at a time, sending proofs down to Cramer's rented waterfront house in Cambridge, Maryland, for Cramer and his wife to read even as Cramer tried to write the next installment.

With the book due off the presses in barely a month, the epilogue remained unfinished. Understand that this wasn't your normal brief wry/poignant/touching commentary of an epilogue. When you've asked your readers to spend 1,000 pages getting to know in an intimate way six of the men who wanted to be president in 1988, giving a glimpse of what happened next in their lives is a crucial part of the storytelling.

And now Cramer's carefully constructed concluding chapter was threatening to collapse like a house of cards. The way he had it written, one story about Michael Dukakis was essential—and the guy on the other end of the phone had said it was off the record. So Cramer was begging, pleading, demanding permission to use it. But the guy wanted the story to stay off the record, out of the book.

Cramer's voice became the instrument of all he had endured in the last six years. There were the thousands of hours of interviews with candidates and their uncles, aunts, cousins, high school sweethearts, college roommates, law school professors, business partners, friends, enemies, mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, wives, children, political handlers, media savants, and virtually everyone else who might have had contact with George Bush, Michael Dukakis, Robert Dole, Richard Gephardt, Joe Biden, and Gary Hart during their remarkable lives that had brought them to the brink of the presidency. He had spent his own money—not that of a newspaper—to trace the lives of these men while chasing after their campaigns, watching the expenses eat up his generous six-figure advance like a hungry 12-year-old going through a Big Mac.

And once he had all this information—taken from tapes and notebooks and memories and read into a tape recorder during an extended stay in Venice, Italy, following the '88 election, transcribed by his research assistant, and finally turned into some 13 million bits on the hard disk of one of his two computers—he found that trying to keep it straight, trying to tell these six stories, trying to be fair to these men whom he readily admits he fell in love with, was like trying to keep 1,000 plates spinning high in the air as an unimpressed Ed Sullivan looked on.

It took its toll. At one point Cramer thought he had a heart attack, then maybe lung cancer. That turned out to be pleurisy. He thought he had liver cancer, did have phlebitis. Half of his face froze up with Bell's Palsy for six weeks. His back went out and for a couple of weeks he had to write lying flat, using one of those space pens. He gained 20 pounds on campaign food and, when the doctor ordered him off the unfiltered Camels he'd smoked since his undergraduate days at Johns Hopkins (Class of '71), he slapped nicotine patches on his body and promptly gained 20 more. In the midst of all this, he turned 40. He got married. He fathered his first child, a daughter, Ruby.

And after all that, now this guy on the other end of the phone was telling him, no, you can't use that story. The epilogue was falling apart and the pages weren't going to make it to New York that day and the book wasn't going to come out.

"You've got to," Cramer was almost shouting into the phone.

"I think he heard my desperation," Cramer said a few months later. "He finally said, 'I've ridden with you for six years on this. You can have it."'

With that Cramer went back to work, clicking away at one of the computers in his garret office as the other one stared blankly onto a room filled with books and tapes and notebooks and microcassettes and fi le cabinets stuffed with newspaper clippings and ashtrays once again filling up with Camel butts as his nerves had driven him back to the tobacco that was once the economic mainstay of the Eastern Shore where he now labored.

Just as he doesn't smoke one of those half-hot-air, low nicotine brands, so Cramer does not approach his craft like one of those two-hours-before-lunch-then-two-more-hours-and-tennis-anyone kind of writers. While his prose style may owe much to new-journalism guru Tom Wolfe, his work habits are more like those of Thomas Wolfe, the southern novelist who used to stalk the streets of his adopted city of New York crying out, "I wrote 10,000 words today! " It was up to famed editor Maxwell Perkins to make sense of it all.

So on that April D-Day, Cramer wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote until his wife came in. This was Carolyn White, his Maxwell Perkins, a woman who in her 20s was managing editor of the newspaper in Columbia, Missouri, who went on to editing jobs at the Philadelphia Inquirer and Rolling Stone, but who quit that to live with Cramer in the mid-' 80s, his freelance days. She had watched their bank account disappear, the lights and phone getting turned off in their New York apartment, as she edited his magazine pieces, mainly for Esquire. ("We lost money on every one of them," he says.) She had kept editing his copy during the three years of writing What It Takes and now she walked into that office and told Richard, "Stop. It's finished. It's over."

He looked up from the computer screen and realized she was right. They printed out those final pages, drove to Baltimore, got on the train to New York, and put them on the editor's desk.

It was now late August and Cramer had been flogging the publicity machine for almost two months. He'd been profiled by the profile writers whose insight he disparages in his book. He'd become one of the quick-hit political pundits he ridicules early and often in the 1,047 pages of What It Takes. He'd done CNN and CSPAN, NPR, and NBC. During the political conventions, you could have caught him one hour giving a piece of analysis for McNeil/Lehrer, the next telling crude jokes from the George Bush repertoire for The Comedy Channel. He hit 14 cities on his formal tour—a morning TV talk show followed by some drive time radio then maybe a noon news and an extended-lunch interview with the local newspaper, a book-signing at a store, some afternoon radio, maybe a live-at-five-style TV appearance, then more talk radio at night.

"I'll do anything for the book," Cramer said.

Whatever it takes, in other words, to move these $28 dictionary-size chunks of prose. The reviews had been polarized between exuberant praise and outright condemnation, though most of the bad notices were written by members of the claque of professional political journalists who are often the objects of scorn in What It Takes.

In fact, What It Takes is a stunning work, one that has the ability to change forever the way you look at politicians, campaigns and their coverage in the press. Cramer approached these candidates not as most of the bottle-fed-on-Watergate baby-boomer press corps does, with suspicion and distrust, certain that evil lurks in the heart of every one and that theirs is the solemn duty to uncover it. Instead he sees the candidates as heroes, flawed and tragic in many cases, but nonetheless remarkable men who have altered the course of events wherever they have strode.

He takes you with them into the arena of presidential politics, where they are put on display in a bubble formed by the cameras and microphones, pens and notebooks, handlers and managers, pollsters and strategists who surround their every move-later shaped into an impregnable shell by the unsmiling security of the Secret Service. Within the bubble, the candidates are pushed and prodded, coached and molded, pulled and stretched, finally beaten mercilessly by the hurricane of attention we focus on them, the howling winds that strip them bare--searching, Cramer would contend, not for their real character but merely for their character flaws.

Few, if any, in the press do what Cramer did, go back to the hometown, talk to everyone who ever knew this guy, try to figure out what he is really like, where he is actually coming from. Cramer says that to compare the standard newspaper profile of a candidate with What It Takes is like comparing a sitcom with a novel. "You should hear the way these guys talk about their work," Cramer said of the political press. "They say things like, 'I got a great line in about Dukakis today.' They live for getting a great line in."

Reduced to begging for scraps from the bubble, the press in Cramer's view looks for that one big hit—the affair, the plagiarism, the draft-dodging—that will take a candidate down so the reporter who did it can bask in praise from his colleagues, as the nation, watching one of its favorite blood sports, howls approval. "We cut these people off from their lives, from everything that they have ever drawn strength from," Cramer says of the candidates. "Then we wonder, when one of them finally gets to be president, why he seems to be so out-to-lunch."

By the time you reach page 1,047, you feel that you have endured the campaign with these people, so intense is the prose, so engaging are the characters, so long is the book. But you're actually sad that it's over, that Cramer stopped when Bush and Dukakis sewed up the nominations, that he didn't take you to the conventions or, except in that crucial epilogue, to the election and beyond. Like the candidates themselves, once you've entered this arena, as merciless as it is, there's a part of you that never wants to leave.

The parallels between a presidential campaign and Cramer's book tour are not lost on him. 'What I feel the most is something the candidates used to tell me, that after a day of getting up early for a breakfast talk, and six more speeches and five personal appearances and 12 interviews, after you've talked and talked and talked until you've talked yourself down to a nubbin, then you finally crawl into your bed in some motel room after midnight and lie there and all you can do is wonder if all that work has done you any good at all," he says. "I think that's why the candidates pay so much attention to polls; it's the one bit of objective evidence that can tell them if what they are doing is having any effect."

Cramer had just finished a week at the Republican convention, talking to any and everyone with a notebook or camera or microphone about any and everything as long as they would mention the book. He'd been up until 3 a.m. wrapping up Bush's acceptance speech, then arose two hours later for an appearance on CBS's morning news. And now he'd flown to Baltimore, one of his hometowns—he's got about as many as Bush—where he had gone to Hopkins and then, after getting a master 's from Columbia, had worked for the Sun for three and a half years. It was at the Sun that he noticed that his byline "By Richard Cramer" was dwarfed by what was under it, "Annapolis Bureau of the Sun." So he added his middle name Ben. His byline thus took on a mix of academic pretention and Mideast mysteriousness that served him well when he ended up covering that area of the world, winning a Pulitzer in 1979, for his next newspaper, the Inquirer in Philadelphia, another of his hometowns.

When he set out on the book tour, Cramer got advice from some of the political handlers he'd gotten to know—what to say, how to say it, the best way to come across on TV. He didn't need to go to them for fashion advice: style has always been a strong point. During counterculture days at Hopkins, Cramer sported the requisite worn jeans and flannel shirt, topped by a trademark orange hunting cap. He re-emerged at the Sun with a white-suit-and-Panama-hat flamboyance that at once honored and parodied the button-down, Ivy League, Brooks Brothers mold of that place. So when he finished the book, Cramer flew to Paris—another hometown from his foreign correspondent days—and bought a nicely baggy, medium green Louis Feraud suit to cover his expanded frame during the tour.

By the time Cramer reached Baltimore, the suit was well-rumpled from its week with the Republicans in Houston. But as he walked to Camden Yards to take in an Orioles game, his white-socked feet shoved into a pair of Italian loafers, a passenger leaned out of a car stopped on Lombard Street. "Hey man, nice suit!" he yelled.

"A good tailor makes up for a lot of things," Cramer commented.

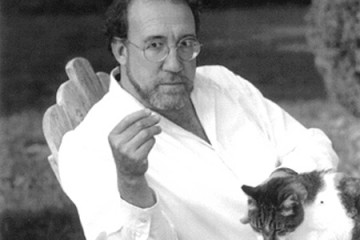

Cramer seemed to relish the exhaustion that came with this tour, staying up after the game for a late dinner though yet another radio talk show host awaited in the morning. By then his bearded face seemed to hang with a droop on the front of his skull, just the way his wire-rimmed glasses hang onto his nose, slipping slightly down beneath the eyes. It is in those eyes that you see the energy, at once impish and quizzical, caring and cynical.

Like the politicians in the campaign, Cramer had reduced many of his answers to formulas that he would insert and play like a cassette, when the appropriate question was asked.

—On the current presidential race (with Bill Clinton well ahead in the early polls). "I always say never bet against George Bush. He'll come after Clinton with a couple of broken bottles. Bush is the most ferocious White Man I've ever met. " (By White Man, a term Cramer uses in the book, he does not mean people of a certain race—though Barbara Bush thought he did and is mad at him as a result—but of a certain class, those that have a presumption that they will rule. These people are often the offspring of big achievers who inherited the ambition gene and didn't have it snuffed out by a wealthy upbringing. Almost all of them do happen to be white men, though under Cramer's definition, a black woman could be a White Man.)

—On Bill Clinton. "I've never met him, but he's proven that he can take a punch. He's a tough guy. I know what hewent through in New Hampshire after the Gennifer Flowers stuff. It would have been a lot easier for him to fold up his tent and go home. The fact that he didn't might mean that he is in this for reasons other than personal ambition, that he has some things he really wants to do for the country."

—On Ross Perot: "Perot is a product of exactly what I was writing about. He came in, pointed to all the other guys with their handlers and advisers, said 'I'm not one of them,' and on that basis went to the top of the polls. Then he hired a couple of handlers of his own, they started telling him where to go and what to say. He took one look at life in the bubble and walked away."

—On why Bush won in '88: "Dukakis tried to hold something back, to keep part of his life. Bush showed that he would hand over anything to be president. Like most employers, the American people gave the job to the man who wanted it the most."

—On the title of his book: "It's a double-edged sword. All these guys go in there convinced that they've got what it takes to become president. What they find out in the end is what it takes from them. Once you've had the realization that you actually could be president and have entered the bubble, your life will never be the same, win or lose."

After the radio interview the next morning, Cramer let his fashion and hygienic sense take over. A week without laundry at the Days Inn in Houston left him in need of some shirts. At Towson Town Center, Cramer first stalked into the mall's bookstores to see where the silver-jacketed What It Takes was displayed, to chat with clerks about its sales, to autograph whatever copies happened to be in the store. Everyone seemed to appreciate that he had dropped by.

Then he went into the going-out-of-business sale at Hamburger's to buy two shirts. He asked the woman who waited on him about her future. What with the store closing, how would she make out? When he learned she was going to work at the new Nordstrom, he gave his personal testimony about what a fine chain that is, how happy she was going to be there. After the transaction, they parted like old friends.

Watching the Cramer charm at work in that men's store, you could envision him chatting up all those aunts and uncles and cousins and friends of the candidates in all sorts of small towns and big cities across America, people who had encountered the powerful personality of a Gephardt or Biden or Dole at some point in their lives, who had loads of stuff to say about him, but had never been asked. And along comes Cramer with a chameleon-like ability to become whatever the situation requires—a friend, a confidante, a son, a father, a brother—so that the person will open up and spill the beans, or maybe his guts.

You can find pieces of Cramer in what he writes about the candidates—Hart's intelligence, Biden's enthusiasm, Dole's determination, and, as was on display at Hamburger's, Bush 's drive to be friends with almost everyone he meets.

Dukakis is notable by his absence from that comparison. Cramer clearly found little common ground with the left-brained, passionless approach to life of the 1988 Democratic nominee. One of the book's telling passages has Dukakis finally rendered speechless by his press secretary as she hammers him for his refusal to take advice, a flaw that turned out to be fatal when he faced Bush.

"He was still staring at her with the look you'd give a misbehaving child ... but he didn't have a leg to stand on," Cramer wrote of the Duke. '"Well,' he said. 'Well ... Well! PUT ON YOUR SEAT BELT!'"

Indeed, though Cramer allowed all the other candidates to read much he had written about them in advance since he was writing from their point of view, he wanted to know if they thought he had gotten it right-he sent nothing to Dukakis. "If I was right about Dukakis," Cramer says, "he just wouldn't get it."

As for Gephardt, that fresh-faced, all-American boy would seem to have little in common with a bearded survivor of the counter-culture like Cramer. But there was this phrase he wrote about Gephardt, one that he uses in interviews to describe all the candidates: " ... he was the heavy lump of iron, and the magnetic field of the family bent around him." Cramer has pointed out that these men are the types who cause others to change their lives--to drop professions, put careers on hold, pull up well-established roots, alter world views—in order to join in their crusade. That power certainly can do harm-to a bright sibling destined to be outshone, to a wife who never wanted to be on display, to an old friend left behind at base camp in the climb to the summit. But its presence is undeniable.

To some extent, it is certainly there in Cramer. Indeed, if there ever was a person with a magnetic personality, it is Richard Cramer. I can still remember the first time we spoke. I had seen him, one of the big cheeses on the Hopkins student paper, the News-Letter, when I did a couple of stories toward the end of my freshman year. At the beginning of my sophomore year, the orange-capped Cramer approached me in front of Shriver Hall, wanted to make sure that I was coming back to work for the paper. Richard Cramer had noticed that I existed! Even then I could feel that meant something. I assumed he was a senior. Turned out he was only a junior. Sometime later I learned he had skipped a grade and was actually my age. I was stunned.

Cramer came to Hopkins in the fall of 1967 because his sister 's boyfriend went there. The couple broke up; Cramer stayed. He gravitated toward the Gatehouse, the small stone building near the Baltimore Museum of Art that served as the News-Letter office.

"It was run by people like Peter Koper, Roger Toll, Elia Katz," Cramer said. "I thought they were giants. I hoped that one day I would measure up."

It didn't take long. At the end of his sophomore year, he was co-editor-in-chief. By that time, Bruce Drake, later of the New York Daily News, now of National Public Radio, had made the News-Letter into a respectable weekly paper. Under Cramer, it started publishing on Tuesday as well as Friday. ('TWICE A WEEK? NO SHIT!" was Cramer's above-the-masthead announcement.) The change required a huge amount of work from a small staff at a small school that offered no journalism courses, no salaries, no tangible rewards for spending most of your waking hours working on this newspaper.

During those days—a heady, and busy, time for student journalists in any case, on any campus, but particularly at Hopkins where the News-Letter was crucially involved in the imbroglio that eventually brought down then-president Lincoln Gordon—it was the force of Cramer's personality that held the paper together. People gravitated to him, worked hard hoping that he would notice, that he would give his approval.

Cramer has remained a big lump of iron, not only to volunteer journalists at Hopkins, but later to Baltimore pols who were courted by this young, shaggy-haired reporter, to almost anyone who stepped into the Sun newsroom during his tenure there-indeed, the newsroom was virtually aligned along the sides of an improbable, very public, romantic triangle formed by Cramer, a fellow reporter, and their boss, the city editor—then to Middle East wise guys and Afghani guerillas while he worked at the Inquirer, to those who knew Ted Williams and Jerry Lee Lewis, subjects of two of his celebrated free-lance pieces, and most recently to the friends and family of presidential candidates.

The book tour ended on the last weekend in August in Cramer's real hometown, Rochester, New York. He had flown from Baltimore to New York for a bit on NBC, then to consult with PBS producers on their election coverage, and finally there was the flight to Rochester, where his parents, Blossom and Robert (who goes by his boyhood nickname of Brud), awaited in the tasteful apartment they moved to after the kids—Richard was the youngest of three, two older sisters, achievers both—had left the nest. Interesting family abounds. Blossom's brother is the jazz saxophonist Steve Lacy who was given a MacArthur "genius" grant last year. Two cousins come from the wealthy family on his father's side. One's wired into local Rochester politics. The other lives on a boat in Europe.

You can see where Richard got the gift of schmooz, from his pharmacist father who used to come home from the drug store every day telling stories of the cast of characters they had come to know so well. This man cruises the social scene with an ease that's matched only by his sincerity. Like his son, 15 minutes after you meet him, he's your new best friend. The distance needed by a journalist must have come from Blossom. She seems to stand back a bit, casting a more wary eye on all she views, demanding perfection.

And you can hear Rochester in Richard's distinctive style of speech—flat tones that remind you this is a Great Lakes city, closer to Cleveland than to the East Coast, but with deses and dats that say, "Hey, we' re still in New York."

Cramer spent Sunday morning playing golf with old neighborhood buddies, then signed books at a funky, eclectic store owned by a high school classmate ("the smartest guy in the class," Richard reported) . That evening, his green Louis Feraud nicely pressed—"That's what happens when you go home to Mama"—he spoke at the Temple B'rith Kodesh, a congregation that last heard Richard reciting Hebrew at his Bar Mitzvah . There was a familial warmth in the room as the tribe welcomed one of its own who had gone out amongst the White Men and come back victorious.

Later, after all the books were signed for all the relatives, each with a personal inscription, even as it neared midnight, with the last three local radio interviews by phone scheduled for the morning—he'd be talking to Colorado, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey—Cramer wanted to go out, find something to eat. He cruised the old neighborhood in the suburb of Brighton, an archetype from the '50s where the Beaver or Ozzie and Harriet could have lived, a safe place of the type that nurtured so many of the baby boomers who would later go in search of danger.

Cramer is not sure what will come next in his career. He could live for decades off What It Takes, joining the pundits on the political talk shows, doing Cramer-style profiles on candidates every four years, selling them to magazines, putting them together in books. He could crank them out the same way Joe McGinniss started producing true-crime books after the success of Fatal Vision. Make a comfortable living.

But Cramer doesn't want that. "If I haven' t said everything I have to say about politics in 1,047 pages, then I'm in the wrong business," he said. "Right now, I owe my bride a lot. She wants to live in Paris, so we'll probably try that for a year.

"I might write a column for a magazine or maybe just spend my bank account down to $200 and then look for a job. I've been poor, so I'm not afraid of that."

As he drove by Brighton high school, Cramer pointed to the ground floor windows of the office of the school paper, the Trapezoid, named after the shape of the building.

'That is the beginning of my journalism career," he said. "Because when you were editor of the Trapezoid you could get a pass to go to those offices any time. Then you could climb out one of those windows and go down to Howard Johnson 's to get something to eat."

Cramer had a cup of black coffee in one hand, an unfiltered Camel in the other. He never bothers to buckle his seat belt.

Michael Hill is a writer for The Baltimore Sun.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged writing seminars, politics, richard ben cramer