Twelve years ago, Johns Hopkins University invited journalist Richard Ben Cramer, A&S '71, back to the Homewood campus to deliver the G. Harry Pouder Memorial Lecture. The invitation seemed to bemuse him. I was in the audience that night at Shriver Hall, and I remember Cramer stepping to the lectern after the usual adulatory-verging-on-fulsome introduction. I must paraphrase from memory, but I recall him saying that while he was pleased to be back, "I figured Hopkins was pretty glad to see the back of me when I graduated."

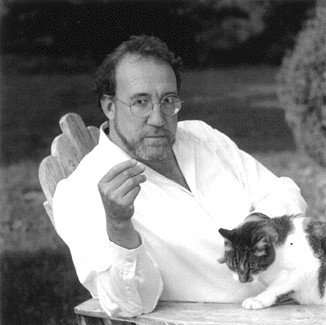

Image caption: Richard Ben Cramer

Ink-stained wretches all over the country, and reporters too young to know what that phrase means, woke up this morning to the dispiriting news that now life had seen the back of him. He had died at age 62, felled by lung cancer. Cramer won a Pulitzer Prize in 1979 for reporting from the Middle East, wrote some fine books, including the epic, 1,047-page account of the 1988 presidential campaign, What It Takes, and scribbled several magazine stories that remain exemplars of the form. When Esquire assembled what it considered the seven best stories it had ever published, Cramer's "What Do You Think of Ted Williams Now?" made the list. He was in fast company on that Esquire roster, with the likes of Gay Talese, Norman Mailer, and Tom Wolfe.

Catherine S. Manegold has written for The New York Times and Newsweek, among others, and knew Cramer as a colleague. "When I came to the Philadelphia Inquirer as a kid in the early '80s, Richard was off tromping about in the Middle East, spilling out work almost every day that left us shaken with awe," she remembers. "Mostly he was a ghost figure then, filing reports from afar. But I remember him back in the office at 400 North Broad once, sequestered on a magazine edit somewhere in the recesses of the building, emerging only occasionally to swear, complain, and suck down unfiltered Camels. He was a gnarly guy who didn't pretend the work was easy."

In 1992, Cramer summarized What It Takes like this: "It was my idea from the first to try to write a real human story about these guys and try to let people connect with them in a visceral way so that they felt with them and exulted with them and felt their tragedy and their triumph." That's a Cramer mission statement, right there. He respected those 1988 presidential contenders (among them George H.W. Bush, Michael Dukakis, Al Gore, and Joe Biden) as giants among men in regard to their ambition and stamina and ability, but they were still "these guys." And this was not just politics. No, this was triumph and tragedy. And this was a human story that Cramer meant to make visceral because you over there, the reader? He wanted you to exult, damn it.

His work was not to everyone's taste, as a survey of his reviews will attest. He was no minimalist. His stories, like those by Wolfe, whom Cramer much admired, were always vivid, pungent, extravagant, and forcefully declarative. He knew what the story was and by god he was going to tell you. I suspect that many of us who are stained by ink, or pixels, either disliked him or revered him in part because he was the sort of figure we'd like to be but are not: smart, funny, irreverent, earthy, shrewd, tireless in pursuit of truth, vigorous in pursuit of life and stories, literary without pretention, and damned fun in a bar swapping stories, some of them true. I called him once, in 1994, after my editor had tasked me with cajoling him into writing something for a special issue of Johns Hopkins Magazine. He politely turned me down, explaining that he had just been immersed in another big project. "I am not in any condition to commit fine prose," he said.

I thanked him, but I did not believe him. He could commit fine prose whenever he wanted to, in any condition.

Dale Keiger, A&S '11 (MLA), is the associate editor of Johns Hopkins Magazine.

Posted in Arts+Culture, University News, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society, Alumni

Tagged alumni, literature, politics, richard ben cramer